A multifactorial, rather than a linear approach has been suggested to understand interspecies variation in states of consciousness (Birch et al, 2020). Where the evidence is stronger, we should generally be more confident. This is a critical approach that considers the strength of evidence in proportion to our confidence that an animal has a feeling.

ANIMAL SENTIENCE HOW TO

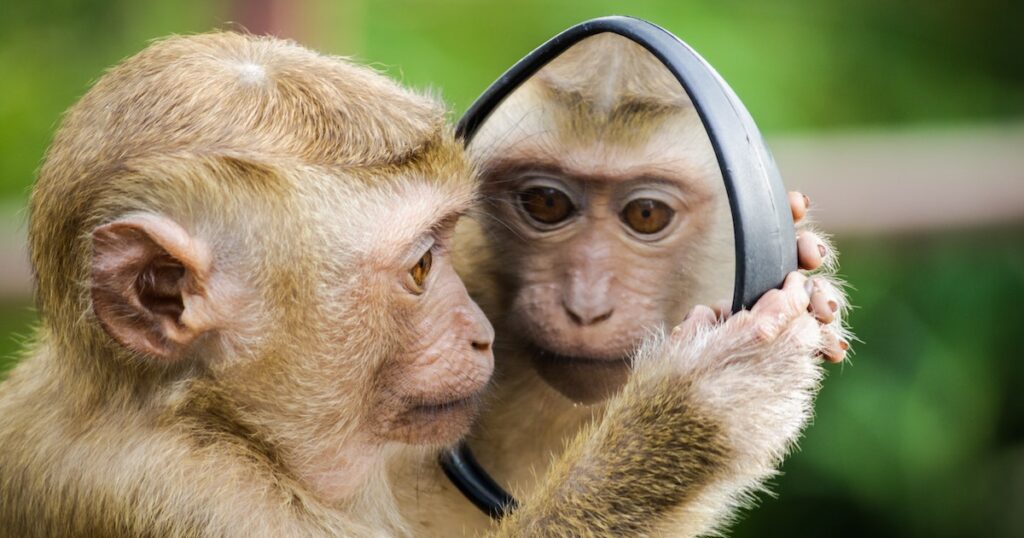

Evidence relevant for ascribing sentienceĪ key question is how to evidence that an animal has passed a threshold where it should be considered sentient? Many scientists consider that we can never be completely sure that an animal is or is not sentient, but only formulate our best belief through the accumulation and review of evidence. In practice, we should err on the side of caution in avoiding suffering, except where this disproportionately increases the risks of suffering for other sentient animals. the benefits of biomedical research to vertebrate patients). if the animals are sentient, what suffering could be caused), and their benefits to sentient animals (e.g. The strength and weight of evidence we consider convincing should depend on multiple factors, including the potential severity of the interventions under question (e.g. We should determine practically what evidence is sufficiently convincing to affect our decisions or legislation, in a sufficiently open-minded, but not overly credulous, way. In ascribing sentience, we should use criteria which we would want others to apply to ourselves, defining "others" in sufficiently generic ways. unthinking presumptions that only certain taxa can be sentient). We should not require impossible "proof" of sentience and avoid over-simplistic categorisations that deny sentience unscientifically (e.g. Avoidable ignorance, metaphysical uncertainty or excessive scepticism are not, in themselves, valid excuses for causing suffering. Our ethical duty to minimise unnecessary suffering implies a requirement to determine, robustly and fairly, which animals are sentient. Cognitive and behavioural capacities may also facilitate evidence of sentience (e.g. However, sentient animals may have different cognitive and emotional capabilities, which means that they have different needs and wants. This definition means sentience is not a particular cognitive process or behaviour per se. There may be a variety of experiences in different animals. These experiences matter to those animals, positively or negatively. The SAWC defines animal sentience as an ability to have physical and emotional experiences. Increasingly, the debate now focuses on which animals meet the relevant threshold, and how that threshold is defined and met. Indeed, modern policy and legislation designed to protect the welfare of animals in Britain and Europe are predicated on an acceptance, underpinned by scientific opinion, that many animals are sentient (Radford, 2001). In some cases, this should be ensured by governmental policy. We have a moral obligation to treat sentient animals as sentient in order to prevent or reduce unnecessary suffering and human activity should consider the impact on animals who are potentially sentient. suffering), and promoting animal welfare means increasing positive experiences and reducing negative experiences. Sentience is a capacity by which animals can have experiences that matter to the animal (e.g. The need to determine which species are sentient is a welfare issue, an ethical issue, and a policy issue. Part 1: Principles for ascribing sentience to animals Background: Why ascribe sentience?

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)